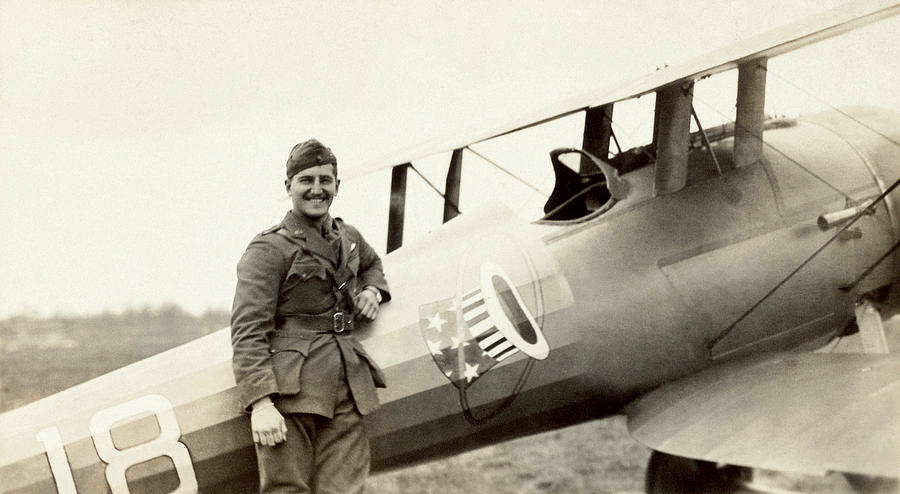

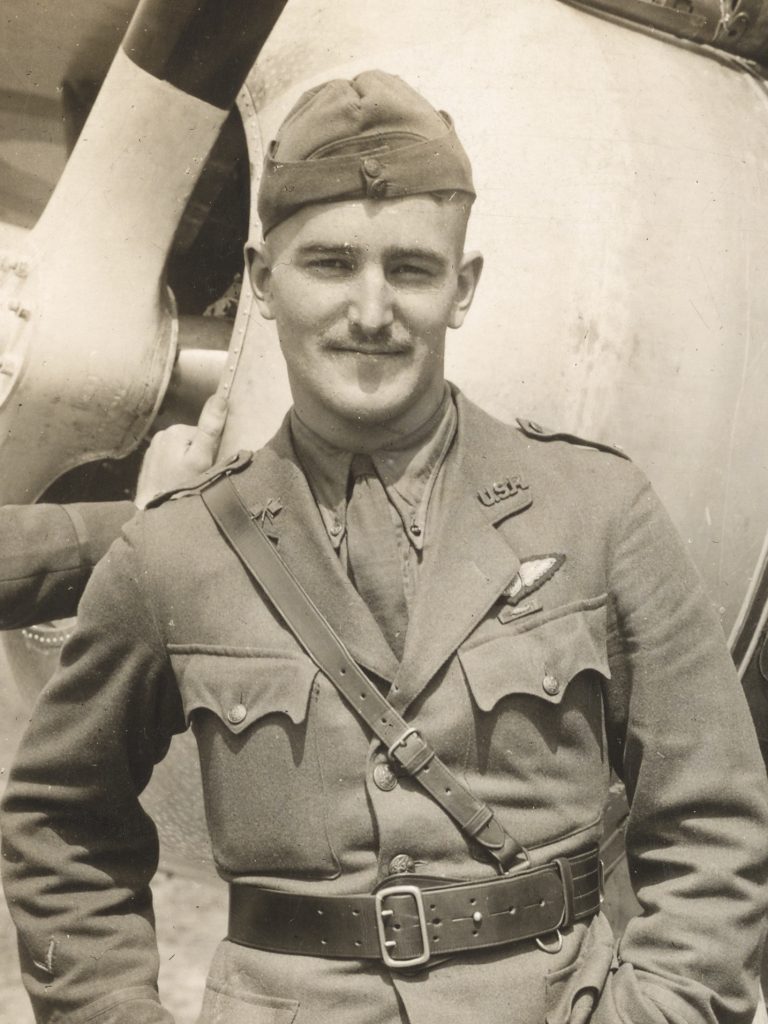

Douglas Campbell was an American aviator and World War I flying ace. He was the first American aviator flying in an American-trained air unit to achieve the status of ace.

Assigned to the Air Service, Campbell learned to fly in a Curtiss Jenny aircraft and was later trained in a Nieuport 28 fighter. He was assigned to the famous Pursuit 94th Aero Squadron (the “Hat in the ring” gang) – at this stage flying Nieuport 28 fighters. Campbell served with Gen. John J. Pershing’s American Expeditionary Forces. He was noted for several firsts in his service. He flew the squadron’s first patrol along with two other famous aviators, Eddie Rickenbacker and Raoul Lufbery. His first kill came while flying in an aircraft armed with only one rather than the usual two machine guns.

On April 14, 1918, his first day of combat operations, he shot down his first German plane, an Albatross soon followed by a second German plane (sharing credit with his squadron mate Lt. Alan F. Winslow) during his dogfight between German pilots and American fliers. This was the first enemy aircraft to be shot down by an American trained pilot.

A few weeks later, on May 18th, Lieutenant Campbell shot down another plane in his Nieuport 28. He destroyed a third on May 19th and a fourth on May 27th. On May 28, he attacked another plane, but its destruction was not confirmed. On May 31, the 22-year-old lieutenant was credited with his fifth confirmed kill and earned the title of ace. He shot down a sixth plane on June 5th. Campbell was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for bravery in aerial combat over Flirey, France on May 19, 1918, and in next 3 weeks received four Oak Leaf Clusters. He was also awarded the Croix de Guerre avec palme by the French military. He scored his sixth and final victory on June 5, 1918.

History of the Nieuport 28

In early 1918, with the air war over the skies of France and Belgium reaching their most dangerous point, American pilots with the Allied Expeditionary Force were anxious to take the fight to the German menace. Unfortunately, the French SPAD XIII aircraft they wanted were in short supply. France had trouble with engine production and the formalization of the SPAD as France’s premier front-line fighter. There were simply not enough of the new airplanes to go around. However, at the same time Nieuport had finished their ultimate biplane design. After almost a year of prototypes and re-designs, production had started on the Nieuport 28 (N28). Since France had no need for the new N.28, the aircraft were deemed as surplus. The American 94th and 95th Aero Squadrons saw an opportunity and began taking the first allotments of the brand new Nieuports in mid-February 1918. This was the first fighter used by American trained fighter pilots.

Click on picture to see the American Heritage Museum’s beautifully restored Nieuport 28 take off on its maiden flight.

American Heritage Museum’s Nieuport 28 restoration

On April 2nd, 2022, legendary early aero plane specialist, Mikael Carlson, flew the American Heritage Museum’s Nieuport 28 C-1 biplane fighter on its first post-restoration flight, taking off from a grass strip near his workshop in Sebbarp, a small village in rural southern Sweden. The airframe, serial number 512, dates from 1918 and is one of just five complete examples known extant. It is also the oldest original airworthy combat aircraft to have served with America’s armed forces, albeit during the post-WWI period.

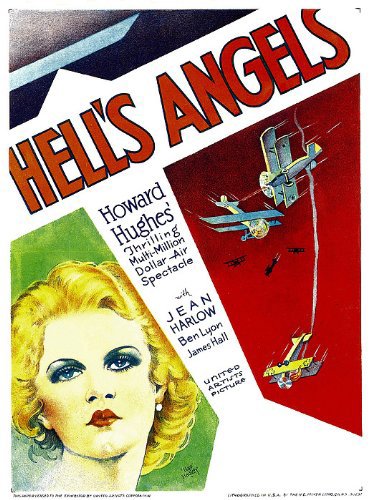

This Nieuport emerged from a factory near Paris, France during late 1918. Following WWI, the American government imported a batch of roughly fifty Nieuport 28s, including s/n 512, to fill out the ranks of the newly-established U.S. Army Air Service. After retirement from  Army use, 512 gained a new lease of life in civilian hands, featuring in a number of significant aviation films, such as Hells Angels (1930) and The Dawn Patrol (1930 & 1938). Part of the collection gathered by famed aerial performers Paul Mantz and Frank Tallman, the Nieuport continued flying into the 1960s, and was amongst the numerous unique airframes put up for disposal at the ‘Tallmantz Auction’ of May, 1968 (there is a wonderful period account of this auction in Time Magazine HERE). Legendary racing car builder/driver, Jim Hall, bought the Nieuport for $14,500, a seemingly paltry sum by today’s standards, but this was more than twice the price which a Curtiss Kittyhawk (RCAF 1082) went for at the same auction, so that should provide a relevant yardstick regarding its actual value. The aircraft has not flown since the early 1970s and largely disappeared from public view until its 2019 donation to the Collings Foundation, parent organization to the American Heritage Museum.

Army use, 512 gained a new lease of life in civilian hands, featuring in a number of significant aviation films, such as Hells Angels (1930) and The Dawn Patrol (1930 & 1938). Part of the collection gathered by famed aerial performers Paul Mantz and Frank Tallman, the Nieuport continued flying into the 1960s, and was amongst the numerous unique airframes put up for disposal at the ‘Tallmantz Auction’ of May, 1968 (there is a wonderful period account of this auction in Time Magazine HERE). Legendary racing car builder/driver, Jim Hall, bought the Nieuport for $14,500, a seemingly paltry sum by today’s standards, but this was more than twice the price which a Curtiss Kittyhawk (RCAF 1082) went for at the same auction, so that should provide a relevant yardstick regarding its actual value. The aircraft has not flown since the early 1970s and largely disappeared from public view until its 2019 donation to the Collings Foundation, parent organization to the American Heritage Museum.

Once the Nieuport 28 was delivered to Mikael, he quickly began the process of evaluating the aircraft’s original structure and condition for restoration to airworthiness. The first order of business was careful disassembly of all components. Being a wooden structure, and more than a century old, it was understood that some parts would be useful only as patterns for exact new-build components. But, to Mikael’s surprise much of the original structure was in excellent condition.

The primary fuselage structure was in fantastic shape, with original factory markings and stampings of the late-war manufacturer, Lioré et Olivier, throughout. Although the stringers and upper bulkheads were not original, and needed replacing, this primary structure was retained. All metal components were also found to be in excellent condition and were used in the restoration. Additionally, the upper wings had been clipped during its use as a movie aircraft by Tallmantz, so Mikael rebuilt a portion of the upper wing to bring it back to original size using the same construction methods that would have been found in 1917.

Surprisingly, the original nine-cylinder Gnome Monosoupape 9N rotary engine was in outstanding condition, despite its age. Mikael was able to break down the engine and, drawing on his intimate knowledge of the type, fully overhaul it. The original cowling for the engine was no longer with the aircraft, having been replaced with an inaccurate piece in the 1950’s. Therefore, an accurate reproduction cowling, a single piece of spun aluminum, was manufactured for the project by a British company using period-correct fabrication methods.

Although the original propeller was intact and in great condition, we decided to craft an exact reproduction of the laminated wood propeller with new glue to use for flight trials. The original propeller will be reserved and installed when the aircraft is placed on static display [at the museum]. The remaining fairings were added, and the cockpit fitted out with original equipment, including a very rare gun synchronizer connected to the propeller. The original machine guns are under restoration in the United States and will be added to the aircraft when it is reassembled here in Stow, Massachusetts.

By early summer you will be able to see this extraordinary WWII aircraft on display in the American Heritage Museum. Even more exciting is the chance to see it fly! If all the conditions are right, we will be flying it during our WWI Aviation Weekend on September 10th and 11th.