The 1909 Curtiss Pusher just out of restoration from Century Aviation, based in East Wenatchee, Washington.

The 1900s took off with a fanatic craze of flying machines. In 1909, Glenn Curtiss introduced his Curtiss Pusher to this growing industry. The elaborately constructed Curtiss Pusher plane captured the imagination of people worldwide. Called a “pusher” because the engine and propeller are placed behind the pilot and, therefore, “push” the aircraft. The Curtiss Pusher represented Curtiss’s engineering philosophy: his aircraft would be an extension of the pilot who flies it.

The Model D Pusher was the first aircraft to takeoff from the deck of a ship, the USS Birmingham on November 14th, 1910 off the coast of Virginia. On January 18, 1911, a Model D was the first to land on a ship, the USS Pennsylvania. Curtis continued to innovate for decades, developing new models of aircraft until his death in 1930.

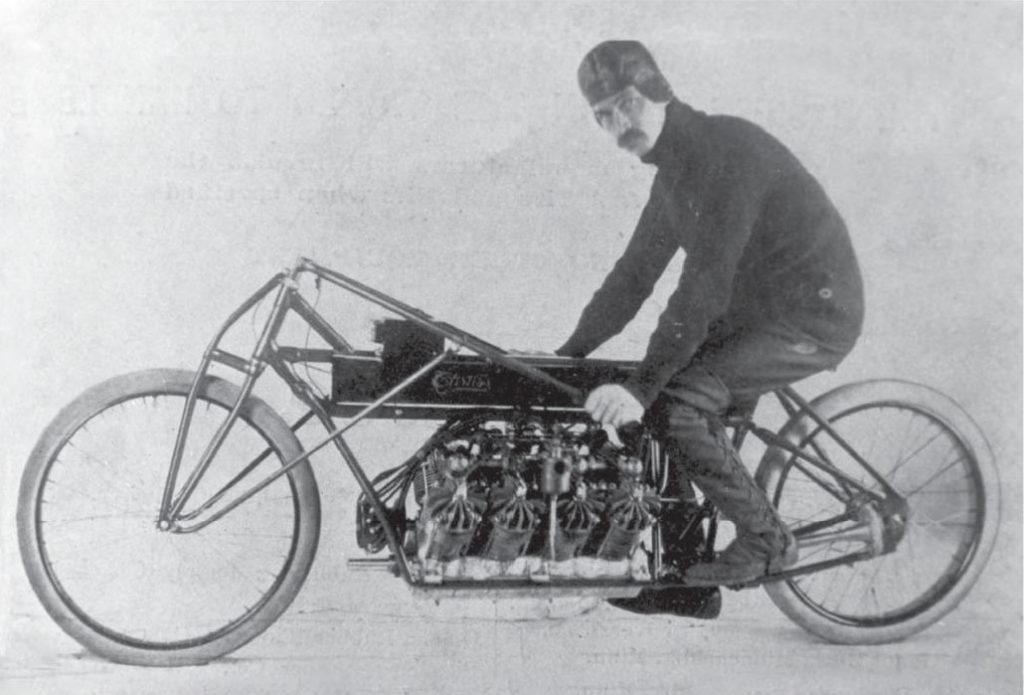

Born in 1878, Glenn Curtiss was an aviation pioneer of the United States aircraft industry. Curtiss began his career building bicycles. Mastering the day’s best technology, he moved on to create intricately designed motorcycles. Testament to his ingenuity was his ability to make the most efficient parts from crude materials. For example, his first motorcycle sported a powerful carburetor fabricated from a tomato soup can with a gauze screen. In 1907, Curtiss raced his V-8 motorcycle to a speed record of 136 mph. His success in engine design propelled him into aviation.

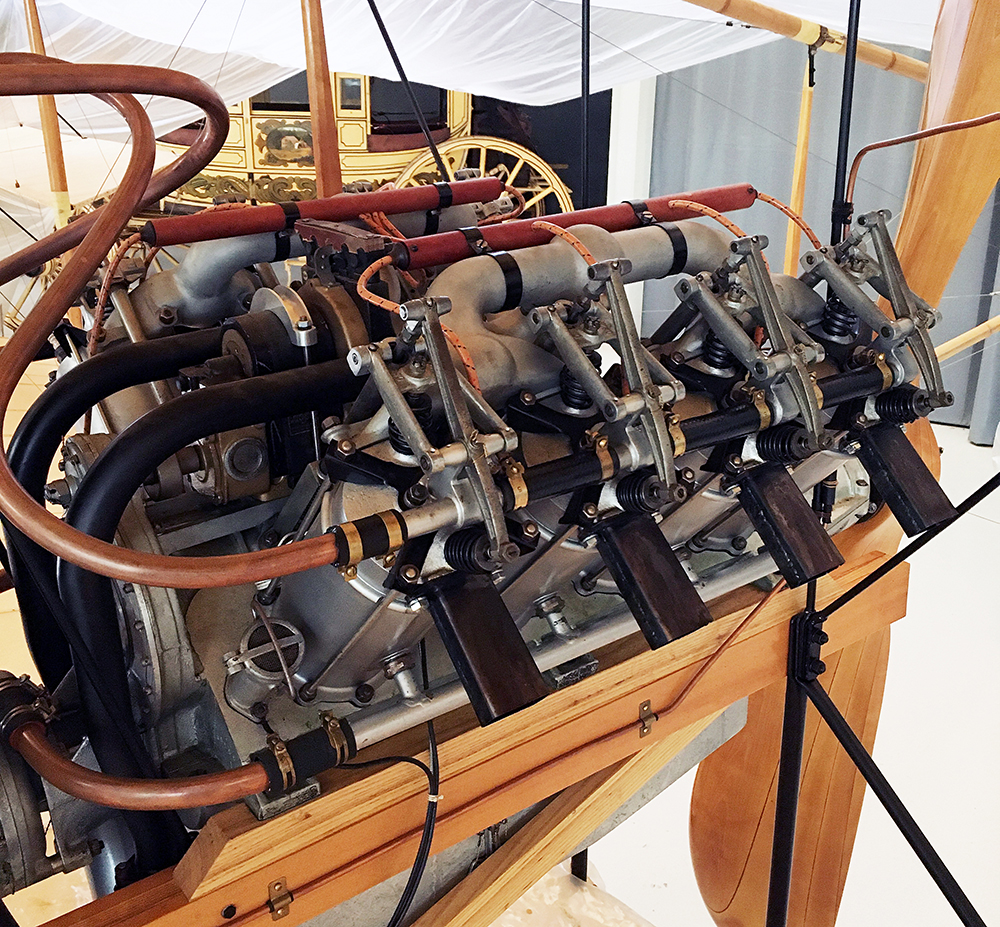

Unique design features of the bi-plane include positioning the propeller and revolutionary Curtiss OX-5 engine behind the pilot. The OX-5 engine was a liquid cooled V-8 that weighed 390 lbs. and could produce 90 to 105 horsepower (if you really pushed it). This was the last in a series of Curtiss designed V engines. Consistent  with most engines of the time, the OX-5’s high temperature areas were built of cast iron. Each cylinder was bolted to a single crank case wrapped in a cooling jacket made of copper alloy and nickel. The cylinders each had one intake valve and one exhaust valve, each operated by a push-rod from a camshaft running between the banks. For the era, the engine was not considered particularly reliable or advanced. Other rotary style engines such as the Gnome-Rhone and Oberusel could produce around 100 hp consistently. Keep in mind any engine of that time was not 100% reliable. Very few fatal accidents were caused by engine failure, although the weak power may have been the cause of many stalls and spins that took many lives during flight training.

with most engines of the time, the OX-5’s high temperature areas were built of cast iron. Each cylinder was bolted to a single crank case wrapped in a cooling jacket made of copper alloy and nickel. The cylinders each had one intake valve and one exhaust valve, each operated by a push-rod from a camshaft running between the banks. For the era, the engine was not considered particularly reliable or advanced. Other rotary style engines such as the Gnome-Rhone and Oberusel could produce around 100 hp consistently. Keep in mind any engine of that time was not 100% reliable. Very few fatal accidents were caused by engine failure, although the weak power may have been the cause of many stalls and spins that took many lives during flight training.

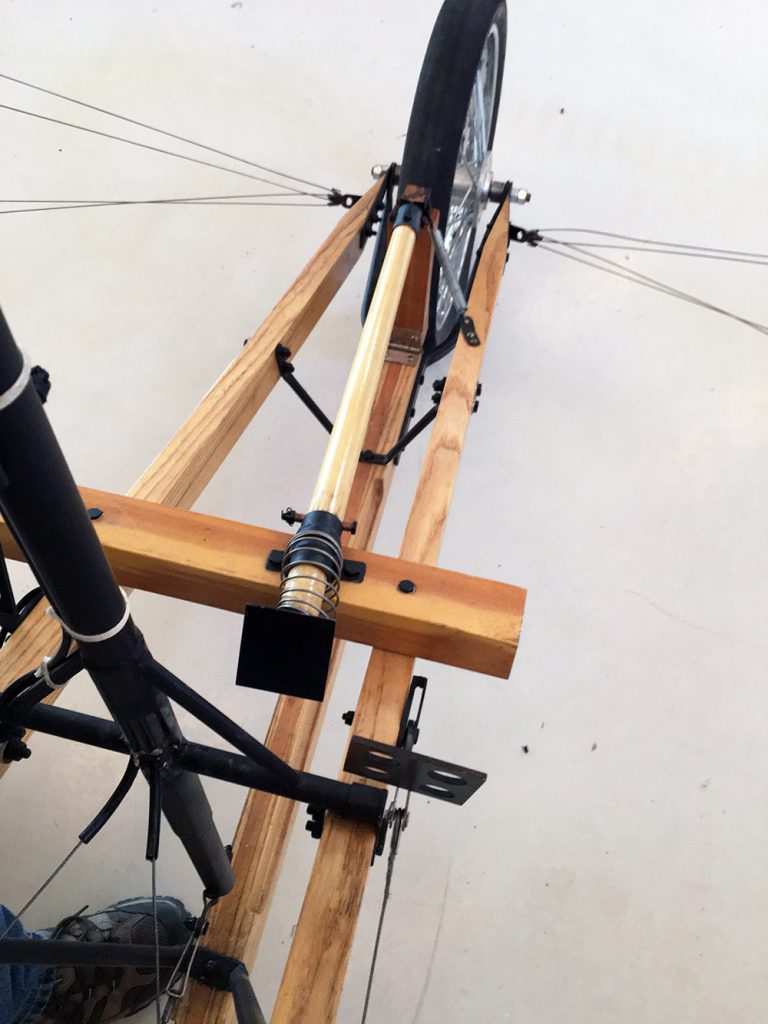

Flying the Pusher required full body movement, quick and agile strength and a level of confidence that can only be found within. At the time of the original aircraft’s production, the Wright Brothers held the patent on the then-state-of-the-art lateral control method known as wing-warping. Since the patent prohibited Curtiss from using this method, Curtiss invented a brand new innovation: the aileron, which proved to be a much superior method of controlling roll in flight, revolutionizing the construction of every airplane that followed it. The pilot controlled the aircraft through a combination of a wheel for rudder, stick for elevator, a foot pedal for throttle, and a shoulder harness attached to the seat for ailerons. The original throttle pedal remains in front of the rudder bar, but a small lever type throttle attached to the seat actually controlled the power in the Pusher’s later years.. Control and support wires and strung across every important structure point.

Original Pusher parts and engines were thought lost to history until the Collings Foundation came across some remarkable treasures; 84 original Pusher airframe parts, ribs and spars in a Massachusetts attic and an OX-5 engine in a Pennsylvania basement. This launched an extraordinary restoration effort.

Century Aviation, based in East Wenatchee, Washington, took on the project. This team of world-class aircraft restoration experts is known for its displays at the Smithsonian and the Air Force Museum. They were pleasantly surprised to find the Pusher Aircraft parts arrive wrapped in August 1915 Boston Globe newspapers. Over a two-year period, Century Aviation had meticulously restored and re-built the Pusher to airworthy condition. This beautifully restored Pusher now sits in the hangar on the Collings Foundation’s grounds in Stow, Massachusetts. We will have it on display during one of our many living history events through the course of the summer and fall – or until this nasty little COVID-19 virus dissipates enough to be able to host public events. Look for more posts on the Collings Foundation’s aircraft and the American Heritage Museum’s tanks in the weeks to come.